A Hero of Our Time

Mikhail Lermontov

Photo credits: Wikimedia

21st November 2020

“A Hero of Our Time” is a novel written by Mikhail Lermontov, arguably Russia’s greatest Romantic poet after Alexander Pushkin. In the Western world, his works have garnered little attention partly because of the difficulty in translating poetry and partly because of the insurmountable reputations of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. Nevertheless, “A Hero of Our Time” is a monumental piece of Russian literature that marked the end of Russian Romanticism and ushered in a new wave of psychological realism that would bring Russian literature worldwide recognition.

His works often express a refined sensitivity for the feelings of fatalistic loneliness, disillusionment and lovelorn loss, yet simultaneously holding an unapologetic ambition for individual mastery of one’s own fate. His life also embodied the spirit of Romanticism in every sense; a talented poet born of aristocratic status and education, who would spend his years of exile in the Caucasus region, and whose life would end abruptly in 1841 from a deadly duel at the age of 26 (following the same fate as his hero Pushkin), tragic yet befitting of a Romantic hero.

Photo credits: livekavkaz

“A Hero of Our Time” was published in 1840, making it Russia’s first fully developed novel of psychological realism. It unfolds a psychological portrait of its anti-hero, Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin, through a series of fragmented stories derived from multiple perspectives.

We first learn about Pechorin’s chronologically final adventure, titled “Bela”, from an unnamed narrator’s Caucasus travel notes. The narrator meets Maxim Maximich, an old soldier, who retells the heart-breaking romance involving the affair of the young soldier, Pechorin, and a beautiful Circassian maiden, Bela. It concerns the curious love-triangle between Pechorin, Bela and a notorious bandit Kazbich, whose prized horse is stolen by Pechorin as part of a ludicrous scheme for Bela, who is similarly kidnapped and betrayed by her own brother. Pechorin eventually wins her love, but ultimately grows restless and dissatisfied by the emptiness in his heart that he thought Bela’s love could satisfy. Bela notices Pechorin’s change in temperament, and in an attempt to regain his affection, she is kidnapped and mortally wounded in revenge by Kazbich. The story ends with Bela’s sudden death which acts as a mortal blow that throws Pechorin into fatalistic despair and withdrawal from society.

From Maxim's story we learn of Pechorin as a gifted yet self-interested soldier who seems to navigate the world through his deep personal impulses. Yet the story is unable to reveal his inner psychology or motives. The second-hand account continues to keep his character shrouded in mystery.

The second tale, titled "Maxim Maximich", takes place in the Causasus sometime after the narrator’s acquaintance with Maxim Maximich, where they meet again by coincidence and learn that Pechorin himself is travelling through the region on his way to Persia. For the first time, the narrator encounters Pechorin in person, who invokes the impression of a cool yet imposing demeanour. Maxim Maximich’s endearing excitement of meeting an old friend is met by Pechorin’s coldness and indifference – who abruptly hurries off before Maxim can even finish his sentence. Maxim who feels betrayed, upset and disappointed quickly attempts to return Pechorin’s journals that he has been safeguarding since the “Bela” incident – but Pechorin is apathetic and leaves without them.

The second account of Pechorin ends with a dissatisfying reunion and prompts the narrator’s intense dislike for Pechorin. But as Pechorin discards his journals, the narrator happens to inherit them from Maxim before his departure and decides to publish 3 extracts from Pechorin’s journals. The narrator effectively surrenders his authority to Pechorin’s personal accounts and allows Pechorin’s enigmatic character to be brought into greater focus. The narrator also explains in the foreword that Pechorin had died on his way home from Persia. Thus, before we even learn from Pechorin himself, the narrative structure is interrupted as we already know that he is dead.

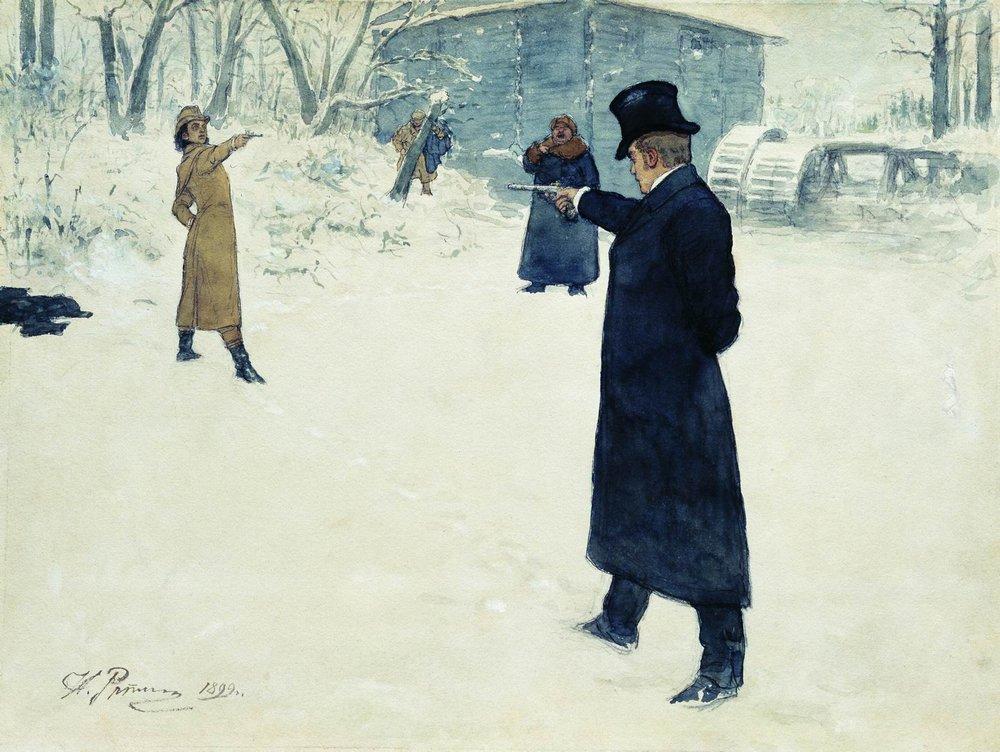

The last 3 stories; “Taman”, “Princess Mary” and “The Fatalist” all happen during an unspecified time before the “Bela” story. These stories progressively reveal Pechorin’s complex personality and inner life to us through his own reports. “Taman” is a short adventure story involving Pechorin’s discovery of a band of smugglers and a seductress who attempts to murder him. “Princess Mary” is a society tale of sexual rivalry detailed as diary entries set in the Caucasian spa town of Piatigorsk, describing Pechorin’s seduction of a fashionable girl, Mary, and his rivalry with an acquaintance, Grushnitsky, another of Mary’s suitors. We learn from the escapade that Pechorin has an incisive understanding of human behaviour and uses this to his calculating advantage. However, the challenge of courtship is further complicated by the appearance of Vera, his former lover and the only woman he has truly loved. Sadly, the story ultimately ends in a fatal duel, dejection and senselessness as Pechorin is unable to act upon his highest feelings. Finally, “The Fatalist” discloses a philosophical thriller that outlines Pechorin’s fatalistic worldview that regards life as a tragic comedy that cannot be overcome by self-determination, also ending in random violence.

Photo credits: Wikimedia

These stories reveal to us an intelligent, talented, but disillusioned and bitter man whose best hopes and aspirations have been thwarted by the unfeeling world. For Lermontov, Pechorin represents the archetypical fallen angel who inevitably causes the downfall of all those around him. But is Pechorin really a victim of hostile fate, or is he a precarious character determined to dominate others at whatever cost? Nevertheless, despite his cold exterior, we learn that Pechorin’s arbitrary decisions always cause him emotional anguish which he attempts to conceal from others. Lermontov’s ability to externalise Pechorin’s jaded character through his calculating yet truthful disclosure of his past is spectacular. For example, when Princess Mary teasingly asserts that Pechorin is worse than a killer and would rather fall victim to a murderer’s knife in the woods than get the rough side of his tongue – Pechorin feigns an appearance of thoughtfulness and responds:

“ ‘Yes, such has been my destiny from my very childhood! You have read on my face the signs of evil qualities which I once did not have; but people assumed that I did, and thus they were born… I was ready to love the whole world, but nobody understood me, and I learned to hate. My colourless youth was passed in a battle with myself and the world. Fearing to be mocked, I hid my finest feelings deep in my heart, and there they died… That was when despair entered my soul. I became a moral cripple – one half of my soul had ceased to exist, had dried out, evaporated, died, and I had amputated and discarded it; while the other half lived and moved, at the service of everyone. And no one noticed, because no one knew of the existence of the half that had perished… If you find what I have said absurd, by all means laugh. I warn you; I shan’t be in the least upset if you do’

At that point I met her eyes, which were filled with tears. Her hand, resting on mine, was trembling; her cheeks were on fire. She pitied me! Compassion – an emotion that all women so readily submit to – had sunk its claws into her inexperienced heart… She’s discontented with herself and accuses herself of coldness. That’s the first and greatest triumph. Tomorrow she’ll want to make it up to me. I know all this by heart, that’s what’s so boring. ”

It is clear that the psychological framework that Pechorin inhabits and uses to navigate the world is characterised by the Byronic schisms – either/or: boredom or pleasure, reason or feeling, angel or demon. However, regardless of that, Pechorin is cynically aware of the uselessness of pursuing lost happiness and his inevitable self-destruction.

Photo credits: hermitage museum

What sustains our interest in the novel is not the disordered fragmentary stories, but rather it’s power to produce an incipient curiosity in the reader for the inner motives of its anti-hero. Lermontov’s command for language brings to perfection the aesthetic qualities of Romanticism, narrative story-telling and psychological realism. The novel is completed by descriptions of the exotic regions of Russia’s expanding empire, the Caucuses in particular, which served beautifully as Russia’s counterpart to Europe’s fascination with the Oriental Middle East. Majestic mountain tops, staggering rivers, shielding forestry, and tribal natives, admirable in their reckless bravery, exotic in their charming women, and alluring in their foreign customs. Though partly biographical in nature, Lermontov asserts in the novel’s foreword (and as the title itself implies) that Pechorin is best understood as an exposition and critique of the psychological condition of contemporary society – this style of societal criticism would be destined to have a long history in Russian culture.

Lermontov’s tragic death in 1841 marked the end of the Golden Age of Russian poetry (or Russian Romanticism) and ushered in a new wave of Realist literature that would inherit Lermontov’s attention to the individual’s psyche and would bring Russian literature to the attention of the world. Regardless of its influence and legacy, the novel itself in isolation is worthy of our attention from a psychological, aesthetic and literary perspective, but even as pure entertainment. It’s a profound study that can be read and enjoyed through multiple angles and perspectives – a classic that must be read by all lovers of literature.

Photo credits: Wikimedia