Anna Karenina

Leo Tolstoy

Photo credits: Pinterest

21st November 2022

“Все счастливые семьи похожи друг на друга, каждая несчастливая семья несчастлива по-своему.”

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

The famous opening lines of Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” introduces the readers to a novel concerned with the family; about ordinary people, dealing with the most ordinary issues of the day, behaving in the most ordinary ways, experiencing the most ordinary joys and sorrows – but more precisely – it is about men and women searching for happiness in their ordinary lives and how their actions ultimately affect that of their own family.

Tolstoy captures the spirit of a whole society as he moves the reader effortlessly through colourful vignettes of city and country life, from one social setting to another. His characters are so strongly individualised that they come across as unique personalities in genuine relationships, expressing real thoughts and emotions. And embedded in this expansive panorama of Russian life are the tragedy of Anna Karenina and the exploration of Konstantin Levin’s spiritual crisis. It is the emotional drama and psychological effects that make the novel so true to life and the characters so human.

Anna Karenina and Konstantin Levin

There is no doubt that the novel’s principal focus is the deeply engaging portrait of Anna Karenina. A beautifully refined woman who travels to Moscow to save her brother’s marriage but risks her very own marriage by falling for the embraces of another man, Count Vronsky. Her choice to follow her romantic desires will destroy her own family and make her a social outcast – all of which will ultimately lead to her tragic end.

But the novel is balanced by the parallel story of Konstantin Levin’s own spiritual quest for meaning and happiness. He is perhaps the character who experiences the uneven cycle of life to its fullest extent. From: falling in love with Kitty Shcherbatskaya, but facing rejection; labouring on philosophical questions, and learning from the peasants of his native land; the renewed courtship and marriage with Kitty; his brother’s untimely death; Kitty’s pregnancy, and the birth of his son; to Levin’s eventual discovery of the meaning of life and the emergence of an assured family life.

Photo credits: meer

Inner Turmoil and Spiritual Struggle

Throughout the novel, we are exposed to Levin’s inner turmoil and spiritual struggle against his own hyper-consciousness of death, all which Tolstoy struggled with in his life during the time of writing “Anna Karenina”.

“But the more intensely he thought, the clearer it became to him that it was indubitably so, that in reality, looking upon life, he had forgotten one little fact-that death will come, and all ends; that nothing was even worth beginning, and that there was no helping it anyway. Yes, it was awful, but it was so.”

If life ends in nothingness, then all actions are meaningless and are of no ultimate consequence. All of Levin’s attempts to philosophise and abstract his way out of the inevitable reality of death are fruitless. No matter how hard Levin tries to grapple with death, he always finds himself further down the dreadful abyss. So much so that he is even unable to be content in family life, to act or find happiness in the event of his son being born – all which eventually leads to his profound depression and contemplation of suicide.

In contrast to Levin, wherein his suicidal thoughts are caused by his fixation on death, Anna’s tragic ending appears to be caused by a very different kind of obsession – more subtle and less explicit than Levin’s but nevertheless there.

A Search for Happiness

Anna and Vronsky’s affair begins with flirtatious exchanges at a high-society ball and Vronsky’s eventual pursuit which results in Anna’s submission to Vronsky’s affection. At this point, she recognises the fatal difference between her stilted marriage and the exciting thrill of her romance with Vronsky. Anna has clearly fallen for the enchantment of the early stages in all romantic relationships, and for this, she is willing to jeopardise her own family's happiness.

However, the deterioration of Anna’s mental health materialises after the birth of Vronsky and her daughter, when in desperation to secure Vronsky’s affections, she elopes to Italy with him. Anna’s desire to retain the spontaneous passion and excitement of their initial romance comes in direct conflict with Vronsky’s intentions to maintain his presence in good society whilst establishing a stable family life. Anna and Vronsky soon realise that their cohabitation fundamentally cannot work, especially when society rejects them and restricts their access to the material luxuries and freedoms they were previously accustomed to. As a result, Anna grows increasingly possessive and paranoid when Vronsky is unable to provide her the kind of love and attention she yearns for.

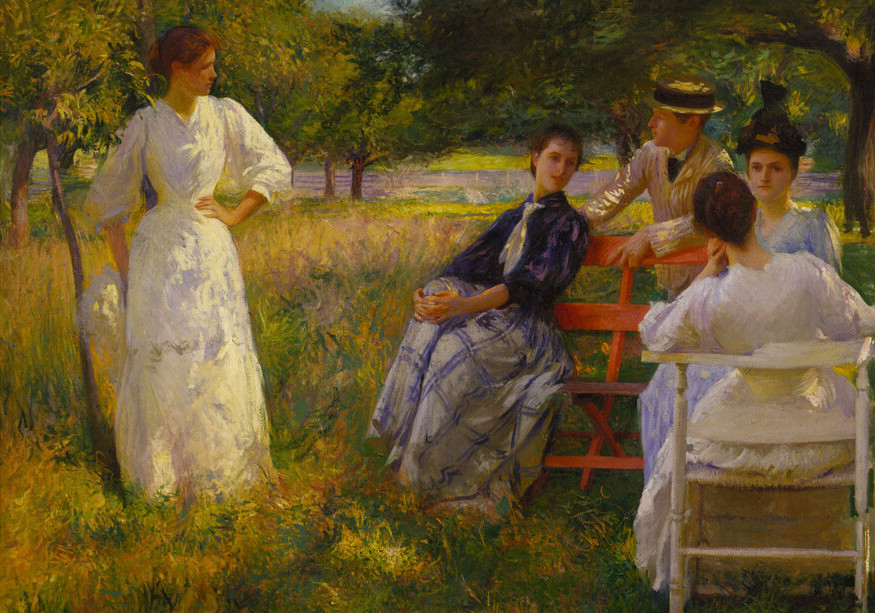

Photo credits: Conversations with the Collection

Anna’s Tragedy in Contrast to Levin's Spitirual Resolution

Instead of Levin’s fixation on death, Anna’s fixation is centred on misguided happiness, a romantic passion long gone, and all attempts to relive this passion are met with intense disappointment. During this process, she effectively abandons her son and husband, and even leaves her new-born daughter behind, only to achieve nothing but disappointment. Although Anna and Levin’s experiences traverse very different trajectories, they nevertheless converge here at the point of deep depression. If all forms of happiness are empty and all actions futile, then life has no true purpose. Her inability to detach herself from her romantic obsession inevitably causes the deterioration of her family and drives her to destroy herself in an act of unfathomable revenge.

“And death, as the sole means of reviving love for herself in his heart, of punishing him, and of gaining the victory in that contest which an evil spirit in her heart was waging against him, presented itself clearly and vividly to her”

As we read of her final moments; we witness her travelling in a railway carriage listening to the innocuous conversations around her. Functioning like a psychological black hole, she swallows and internalises everything she hears, then reinterprets, and applies them to her own situation, all of which eventually push her to her own violent destruction.

As we return to Levin, his suicidal thoughts and spiritual longing is triggered once again by his brother's death. All of which inevitably creates an emotional gulf between himself and Kitty, his new-born son, and all around him. But thankfully for Levin, we are unexpectedly met with a profound resolution to his existential crisis towards the end of the novel when a peasant passes a simple truth to him.

““Fokanych – he’s an upright old man. He lives for the soul. He remembers God.” … At the muzhik’s words about Fokanych living for the soul, by the truth, by God’s way, it was as if a host of vague but important thoughts burst from some locked-up place and, all rushing towards the same goal, whirled through his head, blinding him with their light.”

Fokanych, the upright old man has no need to debate philosophical nihilism, nor does he need to look far to find fulfillment in his life. The key is in his simplicity and good-heartedness in response to day-to-day life. “He lives for the soul. He remembers God”. Though seemingly insignificant, it is the words from the simple-minded peasant that reinvigorates Levin’s religious faith from his childhood and initiates a revelatory change in his perspective.

And with this simple faith, the very ability to notice the beauty and goodness of life's simplicity emerges from his soul. It is the simple joys: ploughing the fields with the peasants, taking walks across the wheat fields, reading books in his study, realising that he truly loves his son, all these bring simple yet deep fulfilment to his family life. As Wittgenstein puts it, “The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity”. It is in the simple and familiar that we can most often find the most striking and meaningful aspects in our lives.

Photo credits: Mature Times

True life is lived not where noticeable changes occur – where people battle and conquer one another, fall dangerously in love, or acquire fame and fortune – but where the infinitesimally small and everyday moments of life take place. It is only when Levin gives up his intellectual abstractions and learns to be truly attentive to the particulars of life does he reach the Tolstoian truth. Unfortunately, Anna’s pursuit of an intangible happiness proves as mistaken as it is seductive and ultimately leads to her downfall.

It is worth noting that only moments before her death, simple memories from her childhood come flooding back to her.

“She wanted to fall halfway between the wheels of the front car, which was drawing level with her. But the red bag which she began to take from her arm delayed her, and she was too late; the car had passed. She had to wait for the next. A feeling such as she had known when about to take the first plunge in bathing came upon her, and she crossed herself. That familiar gesture brought back into her soul a whole series of memories of her childhood and girlhood, and suddenly the darkness that had covered everything for her was torn apart, and life rose up before her for an instant with all its bright past joys.”

Perhaps this is what Alyosha meant in Dostoevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov” when he said, “even if only one good memory remains with us in our hearts, that alone may serve some day for our salvation”. At the very moment of Anna’s death, the most unassuming moments of her childhood spring into her mind, bringing light and harmony into her otherwise self-destructive spirit. Evidently, it is the seemingly irrelevant moments in life, the day-to-day activities of her childhood, that surface from Anna’s subconscious as a true source of happiness held deep in her heart. Regrettably, at this point, Anna’s psyche is far too contorted by melancholic fatalism for this final glimpse of salvation to save her.

Finding Fulfilment in the Simple Things

At this point, it is worth returning to the opening lines of “Anna Karenina”, “All happy families resemble each other; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”. Perhaps we can see now that happy families resemble each other precisely because their lives are filled with ordinary events, all which seem uninteresting and insignificant to the outside observer. But it is in the mundane and ordinary that relationships are built, that meaning is derived and contentment in life is found.

On the contrary, unhappy families are often unhappy due to dramatic events that attract our immediate attention, those that are chaotic, sensational, and outrageous. As individuals, we all pursue various forms of excitement and adventure in our lives, be that thrilling relationships, material luxuries or financial success. Of course, the point is not to avoid such things, but to recognise that such experiences are not necessary conditions for a meaningful life and to re-evaluate what we truly consider to be valuable and important. And Tolstoy would suggest that it is often the deceivingly simple and unassuming aspects of our lives that deserve the most attention.

Tolstoy’s truth finds itself to be extremely relevant today, whether someone is chasing their own happiness or grappling with existential questions. Life is abundantly full of meaning, and finding its meaning is ultimately a matter of where to look and how to look – and as Tolstoy ends his novel, we are left with Levin’s final thoughts grounded in religious truth where one no longer needs to rationalise everything but hold onto simple faith.

“I will still not understand with my reason why I pray, and will go on praying - but my life now, my whole life, regardless of whatever may happen to me, each minute of it, is not only not meaningless, as it were before, but possesses the undoubted meaning of that goodness I have the power to put into it!”

Photo credits: Pinterest