Farewell My Concubine

Chen Kaige

Photo credits: BBC

31st July 2021

“Farewell My Concubine” directed by Chen Kaige, is a historical drama film that tells the story of two Peking Opera actors, Chen Dieyi (Leslie Cheung) and Xiaolou (Zhang Fenyi), whose lifelong friendship is continually tested by anguish, jealousy and betrayal. Despite the reputations of both men as Peking Opera stars, they cannot escape the tumultuous disasters of modern Chinese history, from the birth of the Republic of China to the terrifying purge of the Cultural Revolution. It is a theatrical tour de force decorated by historical and artistic significance that can only be described as a monumental triumph of world cinema.

The film starts in 1924, where Dieyi and Xiaolou’s relationship begins as children at an abusive all-boys Peking Opera troupe. Dieyi, who is abandoned by his mother, finds Xialou to be his closest friend and only emotional support. The opera troupe is largely made up of orphan boys, who are constantly subject to arduous training, corporal punishment and psychological abuse. As a boy who is naturally gifted with softer feminine characteristics, Dieyi is coached to play female roles (as only men were allowed to act in those times), whilst Xiaolou, a disagreeable boy upholds the counterpart male roles. The talented duo endure their hardship together into adulthood, and inevitably develop a very deep friendship. Years of painstaking repetition and rehearsals eventually bring them to stardom as Perking Opera actors in the traditional Chinese opera, “Farewell My Concubine”.

Photo credits: Tumgir

“Farewell My Concubine”, the opera, is heavily intertwined throughout the film as part of the underlying narrative. It tells the tragic story of Xiang Yu, the King of Western Chu (232 – 202 BC) who during the battle for the unification of China is surrounded by enemy forces and is close to complete defeat. Xiang Yu calls forth his consort, Concubine Yu, who understands the devastating situation that has befallen them, pleads to die alongside her master, but her request is adamantly refused. In order to appease and comfort Xiang Yu for the last time, she performs a dance and sings to him in great sorrow. Immediately after the end of her performance, she takes the distracted Xiang Yu’s sword and commits suicide.

By 1937, these two opera characters are masterfully performed by Dieyi (as Concubine Yu) and Xiaolou (as King Xiang Yu), and their reputations as Concubine Yu and King Xiang Yu reach superstardom. However, the boundaries of fiction and reality is not always clear for Dieyi, as Concubine Yu’s loyalty and affection for King Xiang Yu finds itself reflected in Dieyi’s romantic feelings for Xiaolou. Dieyi confesses with desolation, “I want to be with you for life! How about we stay together forever . . . It’s not enough! It should be a lifetime. One day, one hour, or even one second less, makes less than a lifetime!”.

But in contrast to Dieyi's passionate sensitivity, Xiaolou's carefree charisma is unable to see Dieyi as anything other than a close brother. Xiaolou can leave his persona as King Xiang Yu on the stage, but Dieyi, as a man who imitates the sensibilities and subtleties of a woman on stage, cannot help but maintain his fragmented persona of Concubine Yu deeply in love with her King. Sadly, Dieyi’s deep yearning is not reciprocated by Xiaolou and is left to helplessly shoulder this melancholy in solitude. Additionally, their friendship is further strained by Xiaolou’s marriage with Juxian (Gong Li), a headstrong courtesan from a high-end brothel, which fosters tension and jealousy within the confines of the love-triangle. Unfortunately, it is Juxian who truly understands Dieyi's anguish, but the relationship struggles to move beyond cold hostility.

Photo credits: IMDB

Personal conflicts are not the only factors that instigate the turbulence within their relationships, but also the major political events that would shape modern China as we know it today. The film places the lives of Deiyi, Xiaolou and Juxian in the latter half of the China’s century of humiliation, largely characterised by the Warlords Era, Japanese occupation, Civil War and the birth of the People's Republic of China. Every time stability is in sight, a new political entity overthrows the last one and the lives of the Chinese people are immediately uprooted once again.

1937 brings forth Imperial Japan's humiliating occupation of China, wherein the rebellious patriotism and hard-headedness of Xiaolou will lead him to persecution and imprisonment. The Koumintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) eventually defeat the Japanese and spurs on the civil war with the Chinese Communist Party. However, the apprehensive arrival of the Koumintang will find reason to persecute and imprison Dieyi for his passivity during Japanese rule. And finally, in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party achieves victory over the Koumintang and establishes its imposing reforms on mainland China, bringing the civil war to its end.

The turbulence reaches its climax during the Cultural Revolution, where the Red Guards purge all traditional elements of Chinese culture (including Peking Opera) only to replace it with Socialist Communist ideology. The denunciation of individuals accused of bourgeois activity and counter-revolutionary thought inevitably catches up to Dieyi and Xiaolou by virtue of being former Chinese Opera stars. As class enemies to the state, they are both subjected to humiliating struggle-sessions and forced to acknowledge various crimes and accusations before large crowds who verbally persecute and physically abuse them until they confess and inform on each other. The angry mob continuously screams, “Down with Duan Xiaolou! Down with Chen Dieyi! . . . Talk! Talk! . . . If you don't give in, we will annihilate you!”. The psychological heaviness and physical humiliation during the public struggle-sessions will push their lifelong friendship to a catastrophic breaking point of betrayal and disillusionment.

Photo credits: screenmusings

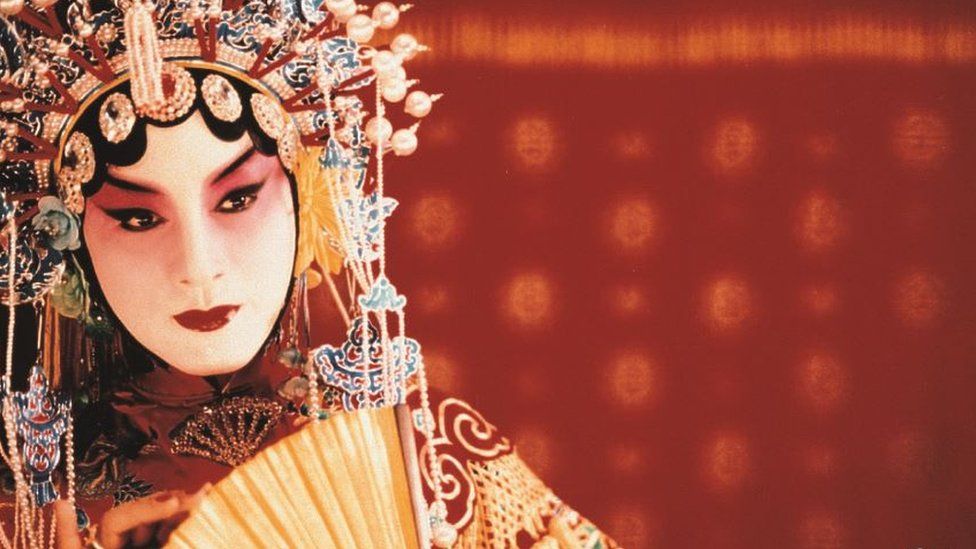

The story and its historical circumstances are tragic and heartbreaking, but it is also worth noting the indisputable cinematic qualities of the film. Peking Opera culture itself is of central importance throughout the film, and consequently, the film is able to educate its Western viewers on the unfamiliar magnificence of Peking Opera. The colourfully intricate costumes are delicately assembled with immaculate attention to detail, the vibrant makeup and ornamental headwear of the actors are mesmerising to the eyes, and the flowery dance acrobatics are masterfully synchronised with the classical Chinese musical ensemble. Each movement in Peking Opera is not without intent and reason, and the singing features long, drawn-out syllables that form melodic passages (often harsh to uninitiated Western audiences). Despite the unfamiliar qualities of Peking Opera's rhythmic musical structure, powerfully expressive singing, delicately meticulous acting and synchronised acrobatics; Chen Kaige has unquestionably woven its brilliance and grandeur into the aesthetic narrative and cinematic atmosphere of the film, creating a unique ambiance that perfectly reflects the emotions and sentiments of the characters and events of the film.

From an artistic perspective, it raises many interesting questions. The film alludes to various classical Chinese opera plays that are considered some of the greatest pieces of Chinese literature. The characters speak of these plays with such great reverence that it wouldn't surprising if they were China’s answer to Homer, Shakespeare and Goethe in the West. It's a shame that much of the Western world will never experience the beauty of Peking Opera, let alone classical Chinese literature, due to its lack of accessibility and the dominance of the Western canon. But how would our modern-day entertainment look like if China had become the primary cultural force in the world instead of America? Our musical, literary and theatrical preferences would be tuned to this obscure poetic structure, singing, acting and dancing - all of our pop culture would derive and emerge from this unique tradition. Yet, we can only dream of an alternative reality. But it certainly does bring into question the cultural legitimacy of other traditions outside of the Wester canon, and how that tradition can evolve today, yet retain the artistic uniqueness of its heritage.

Photo credits: ZBrushCentral

More interestingly is the question of artistic censorship, and whether art can be engineered for ideological ends and still retain artistic merit. In the film, Dieyi enters conversation with the communist youth group about aesthetics and the role of Peking Opera in the modern China. He critiques the Socialist Operas as lacking substance and ambiance, wherein he believes the costumes, song recital, movements and acrobatics are forced and lack character. This, is of course met with uncomfortable hostility, as open criticism of Socialist dogma is taboo. But aside from the circumstances displayed on film, I think this reflects the state of a lot of creative projects in the 21st Century.

Despite today's technological advances and large production value, film studios appear to happily sacrifice original storytelling, talented acting, innovative cinematic techniques, etc. for scripts that lack substance or anything of the above. Film studios would rather promote bad acting with forced virtue signaling or propaganda as long as it makes money. Many films today don't challenge us, and when blatant propaganda is called out, you are suddenly accused of being an enemy of the “virtue” being promoted. More striking is the film's portrayal of the Communist Red Guards and the struggle sessions that the violent crowd uses to persecute and silence everything they disagree with. The similarity with modern day cancel culture is uncanny. It seems people prefer to willfully forget about the past than to learn from it. But I think it’s clear that true art cannot be engineered, forced or created by just anyone but requires those truly gifted to engage in a long and difficult creative process without restrictions.

In the West, when the question of masterpieces of Asian cinema is discussed, Chen Kaige's “Farewell My Concubine” appears to be overshadowed by the likes of Wong Kar Wai, Yasujiro Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, etc. The lack of attention to this monumental work of art is unfortunate, but this should not discourage the viewer from experiencing Chen Kaige's magnum opus. “Farewell My Concubine” brings to light many interesting questions about aesthetics, culture, history and its relevance to mankind. But it is ultimately a complex film about brotherhood, sexual identity, unrequited love, cultural heritage and how individual strife and political upheaval can destroy all these things. It is a glaring insight into how the turbulent events of Chinese history destroyed the lives of its people and culture that couldn't keep up with its changing times. A story of tragedy and heartbreak, not only of individuals but also a whole nation.

Photo credits: screenmusings