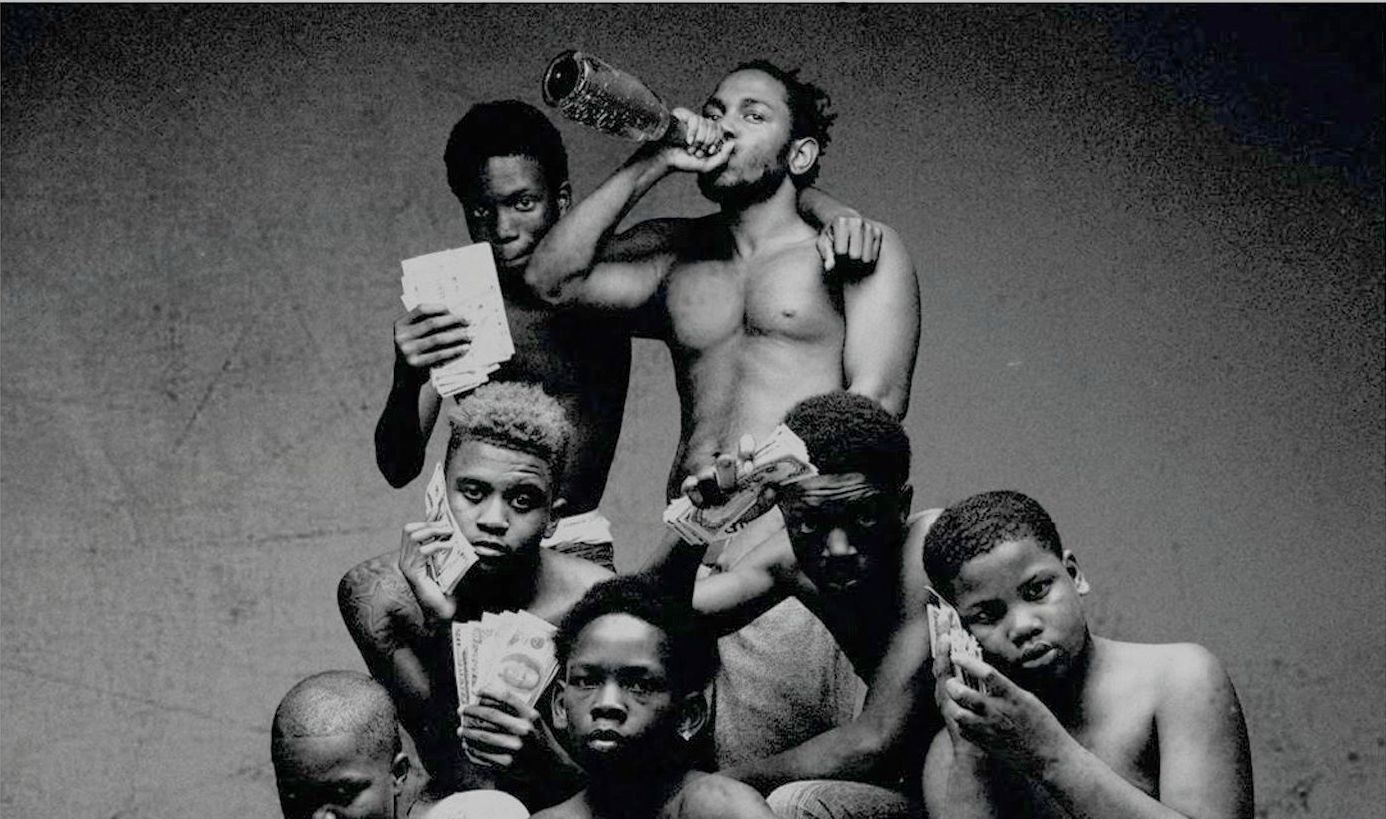

Kendrick Lamar: To Pimp a Butterfly

Photo credits: Vanichi

16th March 2021

“To Pimp a Butterfly” is Kendrick Lamar’s most ambitious and celebrated work to date. Released in March 2015, 3 years after his triple platinum 2012 album "good kid, m.A.A.d City", it was met with widespread acclaim from critics and fans alike and launched him further into superstardom, consolidating his position as the greatest artist of the decade. The album itself makes use of its densely packed thematic scope and auditory landscape to express the African American experience, its long-standing culture and the socio-political issues that plague its communities. But it also presents itself as a poem of Homeric proportions through its lyrical complexity and communication of the Odyssey-like journey of an individual’s struggle through material fame and hedonism, racial discrimination, depression and spiritual helplessness ─ only to find his redemption and purpose on the journey back home. Here, Kendrick also employs a staggering selection of exceptionally talented producers and musicians (Terrace Martin, Sounwave, Dr. Dre, George Clinton, Bilal, Thundercat, Kamasi Washington, and many more) to help craft the project’s monumental sound, which can only be described as the perfect distillation and combination of all African American genres of present and past.

Photo credits: Rolling Stone

During my first listen to “To Pimp a Butterfly”, I was midway through my third year of university, and in those 3 years I found myself listening exclusively to the music of the past (the classics of the 1950s-2000s). So I was completely removed from the contemporary music of the time that everyone else was listening to. I simply wanted to familiarise myself with the masterpieces of the generations before me, and then those of my generation that I was too young to appreciate. This passed me through a labyrinth decorated with the ground-breaking jazz of Miles Davis, Monk and Coltrane, expressive soul of Marvin Gaye, funky momentum of James Brown and the bombastic creativity of Golden Age hip hop. But as a consequence of this musical detour, the geography that I finally returned to in 2015 was entirely foreign to me. However, my timely absence wasn’t entirely fruitless. In fact, I returned with an undeniable appreciation of the African American musical heritage as the sounds of Funkadelic, Charles Mingus, D’Angelo and Tupac Shakur were ringing in my ears. Little did I know, those 3 years would ultimately prepare me for the musical immensity of “To Pimp a Butterfly”.

At the time of its release, I distinctly remember myself at the library preparing for upcoming exams ─ I must have been listening to Jimi Hendrix at the time. Unbeknown to me, I decided to listen to Kendrick’s new album with little exposure or expectation for Kendrick’s musical abilities. To say the least, I was immediately overwhelmed by the creative force and richness of musical connections being set ablaze in my ears. It was as if Kendrick had solved a million-piece puzzle by bringing together all the exceptional pieces of his cultural tradition that I had been listening to for the past 3 years. At that moment, I literally put my pencil down, stopped studying and listened to the whole album back to front without interruption ─ I was simply astounded. It’s impossible not to notice the intricate arrangements of sounds before the lyrical semantics. The influences are obvious; for example, the funky power of Funkadelic/Parliament and James Brown, the moody jazz of Charles Mingus, the soulful rhythms of The Isley Brothers and the G-Funk swagger of Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg. After a closer listen beyond its musical qualities, it is immediately evident that there is a wealth of depth and meaning crisscrossing throughout the album. It is imperative that the album is listened to from beginning to end in order to fully appreciate the artistry and meaning behind this timelessly complex piece.

Photo credits: Vulture

As mentioned earlier, the album functions as an vehicle of poetic discourse, which in itself masterfully contains a poem (titled “Another Nigga”) that unfolds in succession in spoken-word form as the album progresses, bringing context and structure to each song and the album as a whole. From a high-level perspective, “To Pimp a Butterfly” could be said to reflect the archetypal hero’s journey, the culturally universal template used to describe the story of a hero who proceeds through the stages of departure (from home), initiation (through challenges and temptations that ultimately lead to transformation and rebirth) and finally the return home (with newfound knowledge to share).

So, in a similar fashion, the album starts off with “Wesley’s Theory”, a 70s jazz funk mix accompanied by Thundercat’s infectious bassline and George Clinton’s psychedelic-funk vocals. This sets the scene for the story, where Kendrick has “pimped” his way out of Compton, finding himself in the land of fame and fortune. He has escaped the ghetto, achieving the seemingly impossible, yet he is evidently oblivious to his inability to leave his narrow-minded juvenile delinquency behind. This then moves onto “For Free”, which functions as a double commentary on the exploitation of America on African Americans and the musical industry on artists, decisively asserting that “this dick ain’t free”. “King Kunta”, a playful tribute to the G-Funk heritage of Dr. Dre, refers to the fictional character of Kunta Kinte, an 18th century plantation slave. Here he celebrates himself for surviving and leaving the hood, and displays his authority as King Kunta, as he started from the lowest level of society and now sits at the highest. Thus, the first 3 songs illustrate the first stage of the hero’s journey; leaving home, or rather, the proverbial caterpillar “pimping” his way out of his hometown Compton, hoping to leave his traumatic past behind him.

Photo credits: Distract TV

In “Institutionalized”, which immediately follows the boastful high of “King Kunta”, he suddenly recognises the shackles of his distressing Compton upbringing that keeps him enslaved to the almighty dollar and the institutional racism that holds him back wherever he goes. This is perfectly summarised in Snoop Dogg’s outro: “You can take your boy out the hood, but you can’t take the hood out the homie”, as he seems forever trapped by his past. “These Walls” starts off with the first verse of his poem “Another Nigga”: “I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence Sometimes, I did the same”, and is layered by Bilal and Anna Wise's sultry vocals, setting the tone for the song's topic of abuse of power and revenge through sexual exploitation. And “u”, supported by Kamasi Washinton’s avant-garde saxophone riffs and Kendrick’s own distorted vocals, is the darkest and most melancholy song of the album, making it the spiritual breaking point. It is a self-confession of guilt, depression and self-resentment, a battle with his inner demons in the darkest depths of his heart: “loving you is complicated … I fuckin’ tell you fuckin’ failure - you ain’t no leader!... And if I told your secrets the world'll know money can't stop a suicidal weakness”. At this stage, the hero has been introduced to a myriad of obstacles in the form of material temptations and self-conscious abasement, but this also serves as an opportunity for transformation. The caterpillar turns into a cocoon and undergoes the process of self-reflection, setting the scene for its spiritual resurrection into a butterfly.

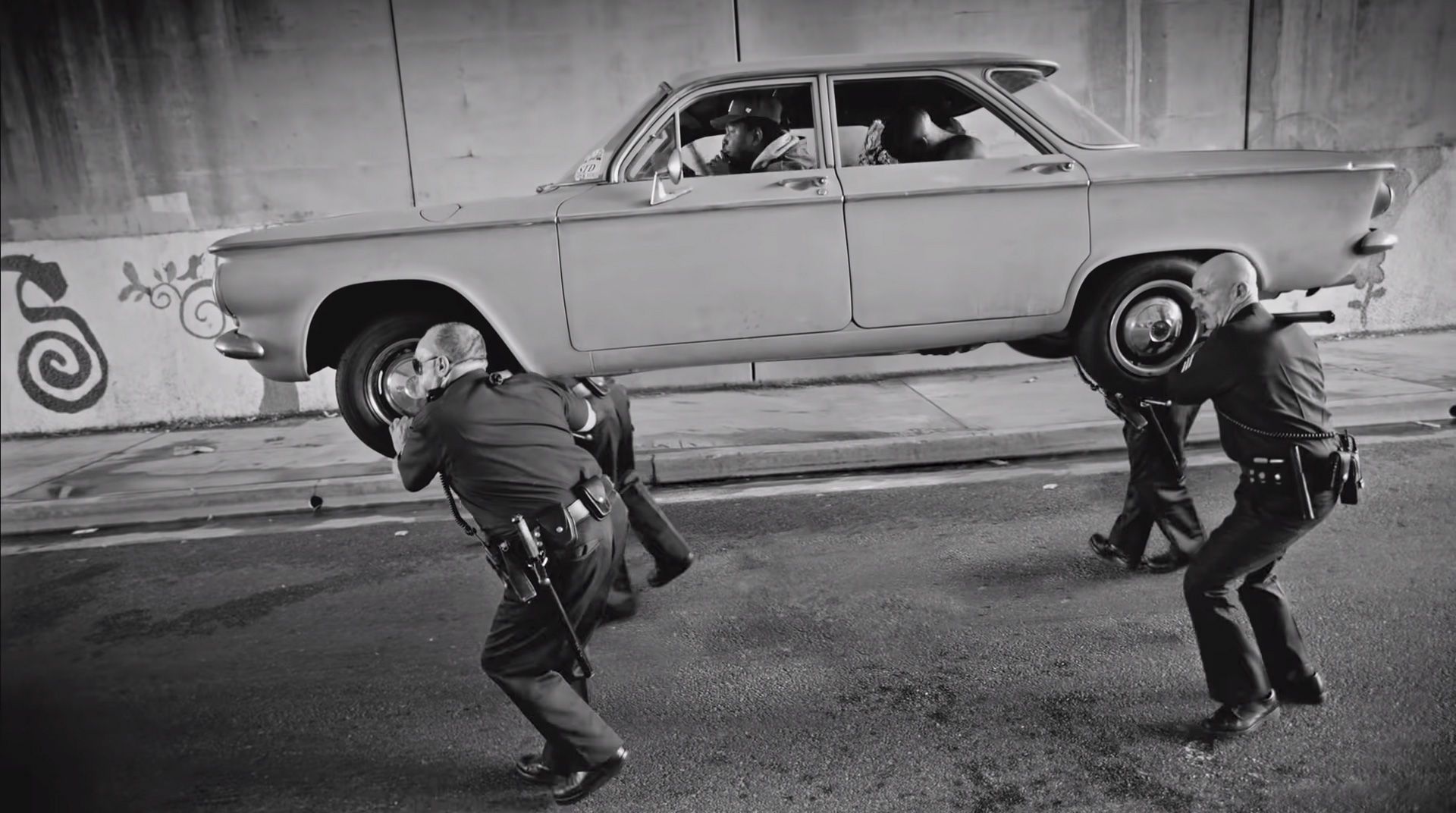

At this point, the album undergoes a series of sudden transitions between diametric opposites; positive and negative, starting with “Alright” providing a moment of hope (in direct contrast to self-destructive “u”). The punchy 808s and Pharell's catchy chorus forms an anthem for assurance in uncertainty; through God, Kendrick acknowledges his failures, but instead of falling into despair, he finds redemption in the knowledge of God's sovereignty and goodness: “I’m fucked up, homie, you fucked up, But if God got us, then we gon’ be alright”. The song also serves as a direct response to the police brutality experienced by blacks that have left many disenfranchised ─ Kendrick encourages his listeners with a message of faith and hope for times of personal and social turmoil. All of a sudden, we have “For Sale? - Interlude”, a dream-like sequence wherein Kendrick's vocal pitch is altered in order to rap in the perspective of Lucy (n.b. the devil, Lucifer), who symbolises the source of all temptations. Lucy's goal here is clear; to saturate Kendrick with promises of earthly pleasures in an attempt to retake possesion of his soul in a Faustian contract. Evidently, God and the devil are locked in a battle over the heart of man, a battle between good and evil that manifests itself as Kendrick navigates between salvation and damnation.

Photo credits: USA Today

“Momma” and “Hood Politics” come up next, wherein we see Kendrick’s personal growth through his reconciliation with survivor’s guilt and his renewed love for his hometown which he so desperately desired to escape in the beginning ─ it's time to return home. However, man is fragile and is constantly susceptible to fall, “How Much A Dollar Cost” illustrates his damning return to his self-sufficient pride and selfishness upon an encounter with a homeless man, only to be humbled by God himself. “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” is a promising celebration of blackness in all shades and hues, but the outro preempts his vision from a distance as he is on the verge of returning to his terrifying hometown: “Barefoot babies with no cares, Teenage gun toters that don't play fair, should I get out the car? I don’t see Compton, I see something much worse, The land of the landmines, the hell that’s on earth”... This sets the stage for “The Blacker The Berry” which expresses an unrelenting desire for revenge and hatred on those responsible for the destruction of African American lives. The heavy hitting drums, ominous instrumentals and Assassin’s threatening verse casts an apocalyptic cloud over our minds, conjuring images of police brutality, institutional racism and the generational consequences of slavery. However, the final couplet reveals Kendrick’s deepest source of despair: “So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street, When gang-banging make me kill a nigga blacker than me? Hypocrite!” ─ the hypocrisy of black-on-black violence itself. Immediately, in calm and cool contrast, “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Momma Said)” finishes the narrative of him returning home, finally meeting his mom, who sees past his braggadocious ego and facade of material wealth, and simply tells him ‘you ain’t gotta lie”, just be yourself. At this stage, it seems Kendrick has undergone the turbulent journey of transformation and atonement, but has returned home as a new man. In other words, the caterpillar is now ready to emerge from the cocoon, reborn as a butterfly.

The hero’s journey is not complete without the hero sharing his gifts with the community, without the butterfly helping the caterpillars. So the album continues with “i”, the spiritual high-point of the album, a clear juxtaposition to the suicidal “u”, it’s direct opposite. Here Kendrick has returned to Compton, ready to give a live performance at a music hall and share the treasures of his journey: “he done travelled all over the world, he came back to just to give you some game”. The Isley Brothers’ sample of “That Lady” gives a flavour of funky psychedelic soul, allowing Kendrick to shower his listeners with immense positivity in the face of Compton’s inherent negativity. It contains a resounding message of self love: “I love myself! ... Illuminated by the hand of God”, in direct contrast to “u”: “I never liked you, forever despise you—I don't need ya!.... Should've killed yo' ass long time ago”. This clearly represents Kendrick’s spiritual rebirth from self-denial to self-affirmation and his newfound faith and purpose in God as he shared in an interview: “My word will never be as strong as God's word. All I am is just a vessel, doing his work”. The live performance is interrupted by the crowd, wherein Kendrick follows up with an acapella reaffirming his black identity by sharing his thoughts on respect, gang violence and the N-word: “Well, this is my explanation straight from Ethiopia, N-E-G-U-S definition: royalty; king royalty”, thus reclaiming the racial slur for one of empowerment for the black community.

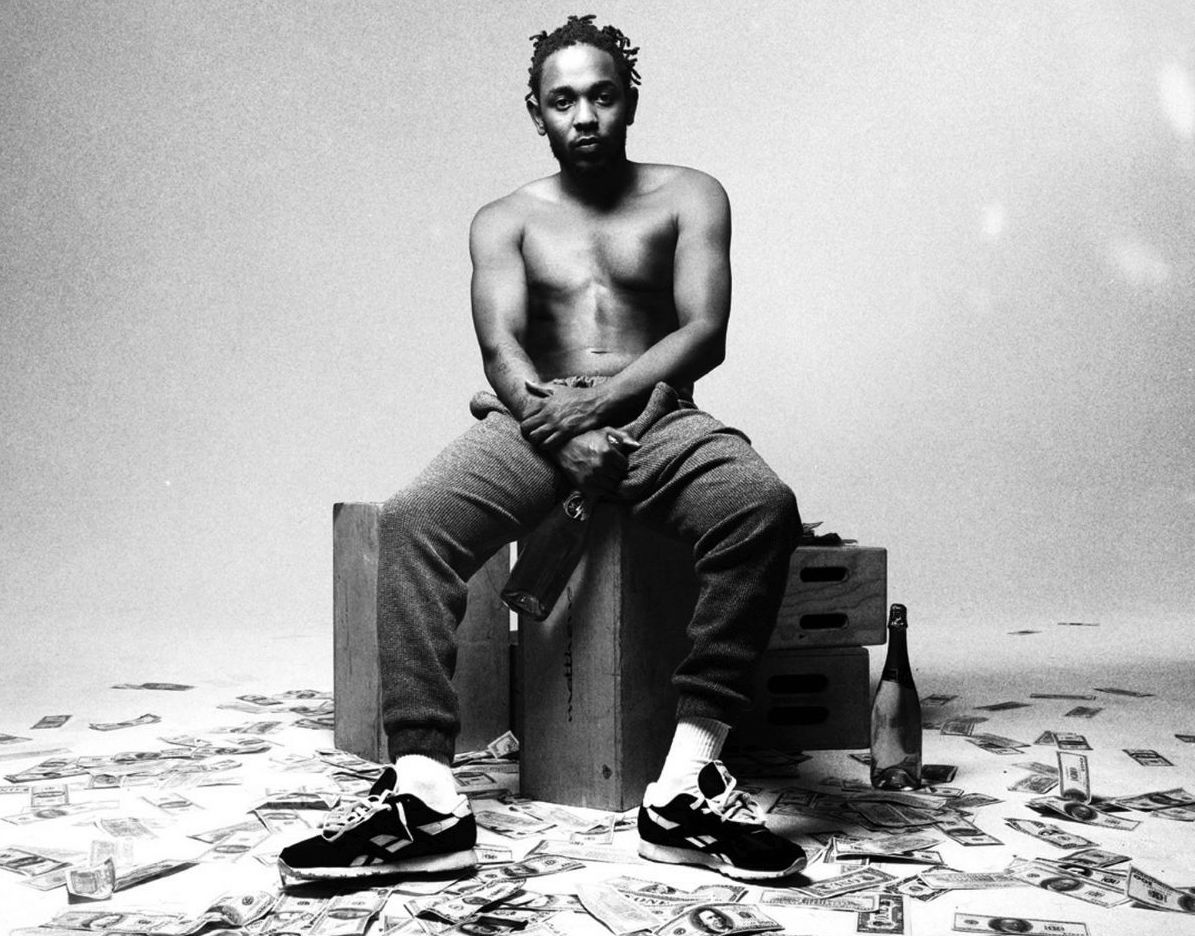

Photo credits: Rolling Stone

“Mortal Man” is the final song of the album; God has triumphantly defeated the devil in Kendrick's heart. However, Kendrick is acutely aware of the fact that man is fragile and the fall from grace is never far away. Having returned to Compton, he inevitably shoulders the responsibility of a leader and is expected to live up to the legacy of those before him; Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Huey Newton. Kendrick recognises his imperfections, the inevitable failures and disappointments he will bring to those who trust him. “As I lead this army, make room for mistakes and depression, And with that being said, my nigga, let me ask this question: When shit hits the fan, is you still a fan?” , will they still love him despite his impending mistakes or the false accusations thrown at him? Ultimately, there is no man without his faults and his burdens - therefore, Kendrick calls us to support one another in love and respect in the final verses of his now completed poem “Another Nigga”: “The word was respect, just because you wore a different gang color than mine’s, doesn’t mean I can’t respect you as a black man, forgetting all the pain and hurt we caused each other in these streets. If I respect you, we unify and stop the enemy from killing us. But I don’t know, I’m no mortal man. Maybe I’m just another nigga” . Finally, at the back-end of the song, we are treated to an unexpected interview between Kendrick and the legendary Tupac Shakur, wherein they discuss with immediate relevance; black culture, racism, fame, faith and love. This is added flawlessly as a perfect closer, tying together the meaning and context of the whole album ─ ending with a final poem by Kendrick summarising the album’s metaphor of the caterpillar and butterfly.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of this album, but hopefully it’s given a good insight into this masterpiece and its extraordinary achievement. The musical qualities of this album are something I haven’t discussed in great detail here, but certainly something that cannot be overlooked. Nothing before it had ever produced such a ferociously vivid depiction of the existential condition of the African American experience through its lyrical content and musical elements. There is no doubt that “To Pimp a Butterfly” caused a paradigm shift to the auditory landscape surrounding it and pushed the art form of hip hop towards new heights. Somehow, the album pays homage to the greats before it yet also emanates an air of undeniable originality. It’s a timeless classic that brings to life the hero’s journey in a contemporary setting, layered with meaning and allusions towards the past, present and future, addressing the timeless struggle and spiritual redemption of the individual in the face of moral, social and political uncertainty. It wouldn't be difficult to argue that this is the greatest album of the 2010s, and Kendrick will forever be remembered as one of the greatest for this work alone.

Photo credits: Baltimore Sun