Russia: the test of a lifetime

26th July 2020

The beginning

On July 2016, I graduated from the University of Oxford with a Master’s degree in Physics. It was a momentous occasion, marking my transition from a youthful student to a working professional in the real world. My friends and family looked at me with great curiosity, wondering what I would do with my academic acheivements, where this prestigious degree would take me. I was simply brimming with potential, and with my fiery eyes pointed towards the future, I saw my life branching out before me. What would the future have in stall for me? Would I become an engineer, management consultant, or maybe a software engineer for the next big thing?

2 months after graduation, despite the confusion of my friends and family, I found myself on a one-way flight to Moscow with nothing but my phone, passport, suitcase of clothes and a Russian language textbook. 6 hours later, I exited the airplane, evidently somewhere far from home... As I headed towards the conveyer belt and waited patiently for my suitcase to appear, I noticed that everyone was speaking Russian, the signs and directions were written in Russian, and of course, the people were Russian! I was actually in the former Soviet capital, with no friends or family, all by myself. After picking up my suitcase, I took the Aeroexpress train towards Belorusskaya Station. This would mark the beginning of my 7-month adventure in Russia .

Why did I do it?

Like every student finishing their last year of University, I had to start planning for the future. What kind of job would I have after graduation? I didn’t have an answer for a long time, but I knew that, if things fell into place properly, I would take a year off.

Having come from a working-class background in South London, the 4 years of studying Physics at Oxford was a unique experience, but also an extremely demanding one. After graduating, I wanted to do something completely different, something ludicrous and as far from Physics and Mathematics as possible - something that would never have been afforded to someone of my background.

Let’s take a year off, why not? But instead of enjoying the unspoiled beaches, ancient temples and colourful nightlife of South-East Asia or exploring the magnificent monuments and tropical rainforests of Latin America, I chose to live through the bleak Russian winter in Moscow. Why? Simply said: I wanted to learn Russian and immerse myself into the culture. It was like I was going on a Russian undergraduate student's foreign year abroad, except that I didn’t study any Russian at university, nor could I speak any…

Visiting Leo Tolstoy's former country house, Yasnaya Polyana, in Tula

How it all began

Why Russian? The decision isn’t as random as it sounds, it was deliberately planned with personal importance on my part. Even though the question of Russia and its culture is largely of no importance to most people, it actually has tremendous significance for me. For over a decade now, I’ve been endlessly captivated by Russia’s literature and culture. Its painful honesty, meticulous awareness, profound depth and spiritual force with which it reveals the most essential aspects of existence is overwhelming.

It all started when I was 16 years old, browsing around a second-hand bookstore. I never liked reading books, but for some reason unknown to me, I decided to buy Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina”. 7 months later, I finished “Anna Karenina” and started reading Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment”. There was something unusually distinctive about these great writers, the way they depict relationships, encounters, landscapes – the multitude of details that make up the human experience. I was simply mesmerised.

Tolstoy and Dostoevsky would introduce me to the works of Gogol, Lermontov, Chekov and more. Literature would take me to History; from the birth of Kievan Rus and the Cyrillic alphabet to Peter the Great’s Western reforms to the terrifying rise and fall of the Soviet Union. Then from History to Music, Art and Film; Rachmaninoff’s expressive Romanticism to Rublev's Russian Iconography, Vrubel’s Symbolism, Tarkovsky’s cinematic poetry, and the list goes on.

The point being, a remarkable world was suddenly revealed to me, and I was ready to learn everything about it. So, over the next 7 years, my spare time would be spent engaged with the greatest works of literature, endlessly relevant lessons of history, and artistic creativity of the Russian people. This fascination with Russian culture somehow brought me to the idea of learning Russian. Afterall, learning a language undeniably gives you an untranslatable insight into its culture and people. I was up for any challenge. I wasn’t only learning a language, I was learning a culture, a way of life and a way to broaden one’s worldview. So that was my goal: to learn Russian and deepen my understanding of everything and anything related to Russia.

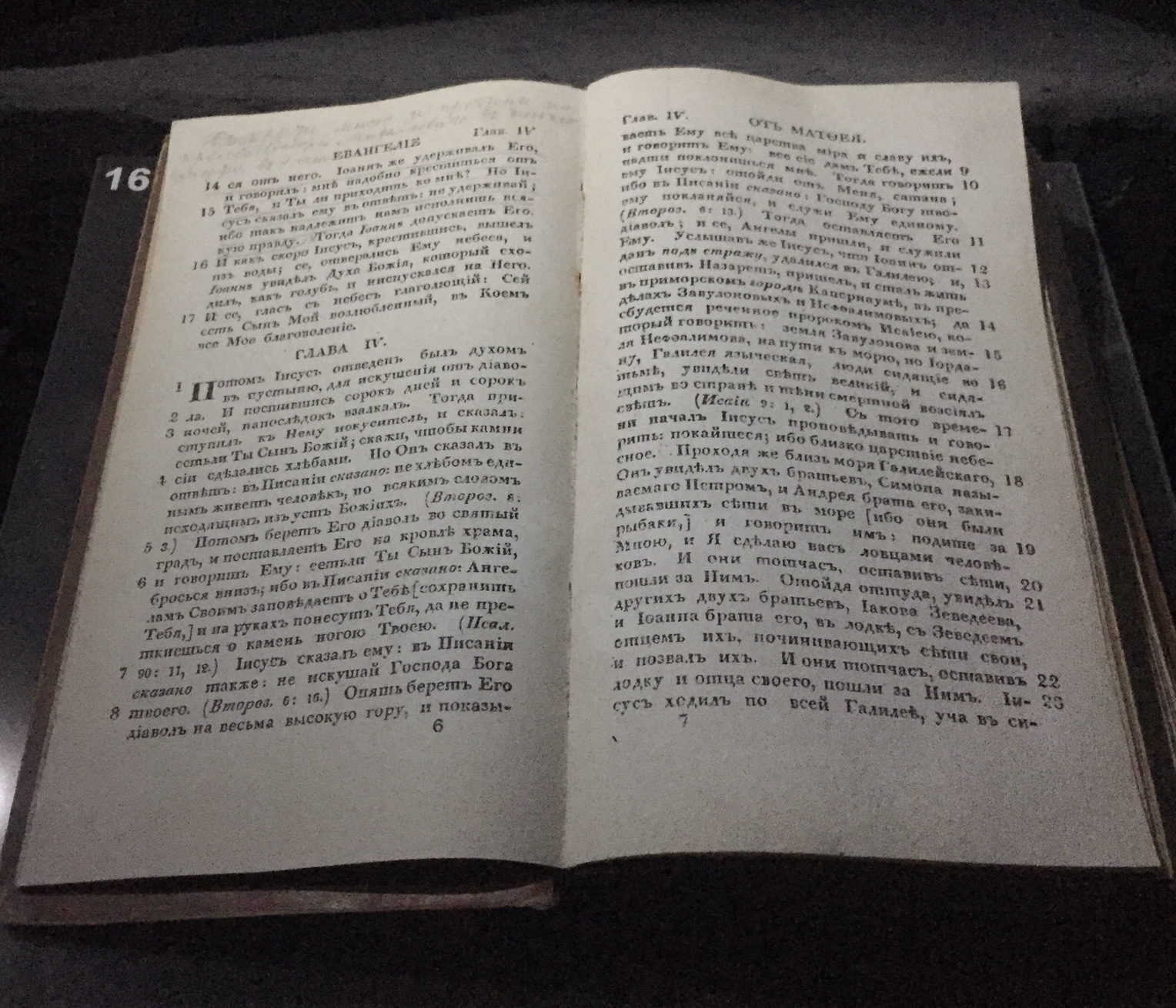

Dostoevsky's bible from the Dostoevsky Museum in Saint Petersburg

Making it work, or at least trying to…

Before I arrived in Russia, I found a way to finance myself by getting a job as an English, Maths and Science tutor for Russian oligarch kids in Moscow – teaching everything in English, not Russian, of course. At least that relieved the burden of worrying about finances.

Aside from the evident language learning challenges, I arrived in Moscow with no friends or family, no understanding of the geography or the way things worked. How do you make friends in a big city when you don’t even speak the language? In short, all kinds of language events, meetups and random chance occasions. Sadly, there weren’t many locals that were interested or willing to help a foreigner to learn their language. I found that Muscovites generally keep to themselves and can seem more ruthless than the Russian winter at times. However, I will say that when you do break through their cold exterior, they are extremely loyal and sympathetic.

But I’m not going to lie, I didn’t make many friends in the first 3 months, and I was often alone. Those first 3 months were the most difficult 3 months of my life, even more difficult than preparing for my final university exams. I was far from home and didn’t have many friends; I was really struggling and frustrated with the language; I wasn’t accustomed to the culture and winter weather (-30 degrees Celsius at worst); and at one point I got very ill. I was lonely, dissatisfied, physically drained and mentally exhausted.

Izmailovsky Park in Moscow

Learning how to learn a language

While my motivations for learning Russian may have been admirable, they were overly ambitious. With practically no knowledge of Russian, learning the language was infinitely more difficult than I had anticipated (why would it be easy anyway?). All I had was a Russian language textbook, the occasional assistance of Russian people and the internet to help me. At that time, I was 23 years old, with no experience of learning foreign languages (I didn’t even get a French GCSE), I hated learning languages growing up and I had spent the last 6 years exclusively studying Mathematics and Physics. You couldn’t get any further from foreign languages than this! And of course, Russian is notoriously difficult for English speakers due to the complex grammar, pronunciation and unfamiliar vocabulary – believe me, learning the Cyrillic alphabet is the easiest part.

Despite all the difficulties, my absurd determination to master Russian kept me from giving up. So, there I was, a hard-trained physicist with zero foreign language skills, very few friends and plenty of time on my hands. I had to “learn how to learn a language,” it’s a thought that never comes across your mind as a child – children just absorb languages like a sponge. For example: I had to learn to pronounce new sounds, listen out for different intonations and vocal inflections, memorise a huge body of vocabulary, decipher and put together words and sentences and translate back and forth between Russian and English in real-time conversations. You could say I was 15 years too late... but that wasn't going to stop me.

VDNKh park in Moscow

I had no experience, guidance or support when learning Russian, and I didn’t want to pay for any lessons. But I knew one failsafe method for independent learning from years of painstaking study at Oxford: simply sit down with a textbook – read, practice, revise and repeat for hours on-end until you’ve mastered the topic. So that’s what I did! I would spend hours every day, by myself, with a Russian textbook in my Moscow apartment room; learning new vocabulary and grammar rules, repeatedly writing out lines and lines of sentences and exercises in Russian as if I was doing time in the GULAG and speaking to myself and Google Translate like a madman. Every time I was introduced to a new grammar rule, I felt like I was being beaten by labour camp guards. It was a strange game of cat and mouse, where I was simultaneously my own prisoner and prison guard.

But in addition to the prison-style studying, I was actually living in Moscow! I would literally read every single sign on the streets, eavesdrop when random locals were speaking about their groceries, weekend plans and children, and attempt to translate every thought in my head from English to Russian. Of course, I'd occasionally force locals to speak to me in Russian even if they were reluctant. During this time, I lived and breathed Russian.

I felt like I had to climb Mount Everest with no climbing equipment or experience, but every single step, despite how small, was still one step closer to the summit for me. For me, any small sign of my Russian improving was infinitely uplifting. The most encouraging and delightful experience for any foreign language student is to successfully communicate with a local in their own language. Every time that I was able to hold a conversation in Russian, it would be small victory for me, proof that my hard work paying off. For example: meeting new people, successfully haggling for a lower price at a street market or bargaining with policemen when they threaten to lock you up. And of course, every time you make yourself sound like an idiot, you remember and never make the same mistake again. I was undoubtedly becoming more confident with my Russian, more accustomed to the rhythm of life in Moscow and coming to appreciate the beauty and expressiveness of the Russian language.

Winter turns into Spring

Well, 7 months later, the snow was melting, the sun was shining brightly over the city, and I had effectively picked up a new language from scratch. I eventually made good friends in the big city and had found myself a tight-knit social circle made up of ex-pats, Muscovite locals and university students from various regions of Russia. In times like these, you realise that friendship is undeniably one of life's greatest good, the most natural remedy for loneliness and excessive solitude. My time with these good friends would leave me with distinct memories of conversations, laughter, trips around Moscow region, chance encounters and a better understanding of the Russian people. So, I eventually found myself able to hold hour long conversations in Russian, express my sense of humour and argue with taxi drivers and haggle for lower prices at the markets. In hindsight, it was a pretty intense way to learn such a difficult language. I basically jumped into the deep end, all alone without any support or guidance. I couldn't have made this language learning experience any more difficult for myself.

Arkhangelskoye Estate in Moscow

A worthwhile test of a lifetime

My time in Russia also allowed me to travel around Moscow Region (e.g. Yaroslavl, Tuva, Rostov, Vladimir), visit St. Petersburg and also take the Trans-Siberian railway, stopping by Perm to visit old friends and Novosibirsk on the way to Irkutsk and then Khabarovsk (before flying to Tokyo). Ancient kremlins, beautiful monasteries, brutalist architecture, unkept post-Soviet buildings, museum-like metro stations and the tranquillity of the Russian wilderness – I saw it all. These experiences have unquestionably intensified my passion for Russia’s culture and people, leaving a much deeper connection than before.

After those 7 months, I had decided to spend the rest of the year travelling the world. At one point, I managed to make a detour to central Asia, discovering Kyrgyzstan, Xinjiang region of China and Kazakhstan. Central Asia is a fascinating yet bizarre place, the nature of the mountainous region is simply breath-taking, and the remnants of the USSR are everywhere, mixed with their cultural heritage. Everyone speaks Russian, but everyone looks Asian. Of course, being able to speak Russian in the ex-Soviet satellite states was extremely helpful, otherwise it would have been impossible to move around. Some of the other countries I travelled to include Poland, Ukraine, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand, Nepal, India, etc. Perhaps this will be subject for another article at one point.

Needless to say, the year was full of unforgettable experiences and challenges. It was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done, a test of a lifetime. This all started at the age of 16 when I picked up the English translation of “Anna Karenina”. If you told me at the time, that I'd spend the next 7 years reading everything I could about Russia literature, history and culture, and then live in Russia after graduating with a Masters in Physics only to learn Russian - I would have thought you were crazy. But all of that really happened! And since returning from Russia, I've read a few Russian classics in the original: Chekov’s “The Seagull”, Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” and “Anna Karenina”... Yes, "Anna Karenina" in the original Russian! So, I managed to go full circle! Starting with "Anna Karenina" in English and then coming back to it in Russian 8 years later.

The whole experience forced me to upgrade my machine-like discipline and taught me that there is nothing I can’t teach myself as long as I genuinely want to learn it. I've developed good language learning skills, and also a greater appreciation for foreign languages that I didn't have before. Now, I simply try to maintain and improve my Russian by reading Russian articles, listening to Russian podcasts and attending language events. But I think I can confidently say that I survived my self-imposed exile with pride, dignity and clarity of mind. Russia will always have a special place in my heart and be of tremendous significance to me whether people understand it or not.

One of my last photos in Russia of the Angara River in Irkutsk